The off-season (November-March) at the Good Sweet Earth homestead is the time of year we like to recharge our batteries and expand our knowledge base. That means a little travel, a little rest, but also a lot of continuing education, research, workshops and reading. Steve (our lawn guy), has decided to focus on two areas of study this year: Learning as much as he can about common lawn weeds found in Michigan, and the physiology of ornamental grasses. That means, in addition to the usual reading about faming, soils, microbes, turf and vermicompost, he’ll be entering the 2020 growing season (hopefully!) with a whole new level of understanding of ornamental grasses and weeds, and how those relate to a healthier, more beautiful yard. So while some of our outside learning comes in the form of classes, much of it comes from good old-fashioned trips to the public library, and browsing the shelves for good books to fill the cold winter months. We thought we’d share with you some of what we’re reading this January, and how it’s informing and inspiring us as we enter a new year.

0 Comments

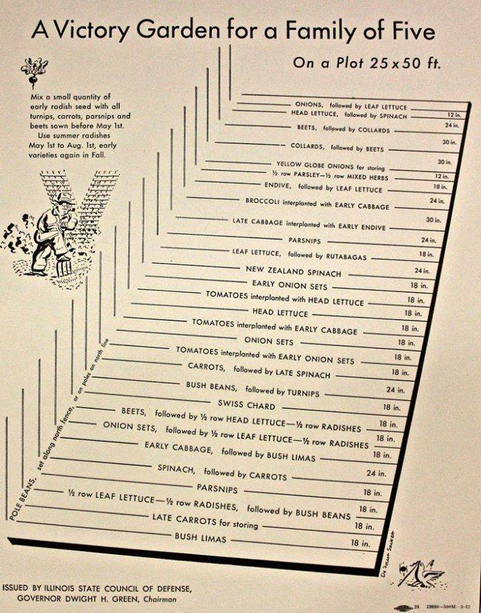

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Victory Garden. In case you’re unfamiliar with this bit of agricultural history, here’s a quick summary: Victory Gardens became popular during World War I as a way to ease demand on the public food supply, as well as boost morale for Americans struggling through a major war. The Victory Garden campaign was then resurrected during World War II for all the same reasons, but this time, it spread across European nations as well. The government, during both wars, encouraged families to grow fruits and vegetables in their yards, as well as in community gardens. The idea to encourage backyard and community gardens sprung from the need to increase food supply at a time when our agricultural resources were being shifted elsewhere, and transportation facilities were needed for the war effort. Every family that grew their own tomatoes, carrots, berries, herbs and cucumbers did so because they truly felt like their backyard garden was contributing to a larger cause. President Woodrow Wilson said, “Food will win the war.” So what does this have to do with us today? Is there a place for Victory Gardens in 21st century America? Well, let’s think about this: there might not be a great American war raging in the traditional sense, but what about a war against corporate greed? Unsafe farming practices? Chemicals invading our environment and polluting our water supply? An economic culture that forces us to rely almost exclusively on corporations for our well-being? Worker exploitation? What if we started fighting for the small family farmer? For a cleaner watershed? For an environment with less greenhouse gasses? For healthy soil that won’t erode when the wind blows? For produce grown in an environment that didn’t exploit labor? The more food we grow ourselves, the less we rely on corporate supermarkets, shipping companies and corporate mega-farms for our food. For every tomato we grow ourselves, that’s one less tomato that had to be trucked across the country in a hot semi from a corporate farm to a chain store. The more organic fertilizers and soil amendments we use, the less we rely on multi-national chemical companies to feed our plants (and ruin our soil). For every bag of Worm Compost, or alfalfa meal, or biochar, or fish emulsion, we use, that’s less money going into the pockets of billion-dollar chemical companies. Natural fertilizers and amendments also replenish the microorganisms and organic matter in the soil that chemicals destroy. The more we shop from local farms, co-ops, CSAs and farmers markets, the more of our money stays right here in our own community. For every bundle of radishes you buy directly from the local farmer who grew it, that’s money going to a family that lives, plays, works and goes to school within 50 miles of your own home. So, you want to do your part to heal the planet? Rely less on corporations for your food. Rely less on laboratories for your fertilizer. Rely MORE on locally-grown organic food—that either you grow or a small family farmer has grown for you. Let’s re-introduce Victory Gardens for the 21st century— the war might not be the same as it was a hundred years ago, but if we lose this one, what kind of planet will we leave for our kids? If you’d like to grow more chemical-free food for your family this year, check out these Good Sweet Earth products, or (if you live in West Michigan) hire your own personal garden consultant to walk you through the growing season. If you’d like to buy some local produce, here are a few local West Michigan sources we love that you can try out this year as well:  Clockwise from left: Mistletoe, English holly, winterberries, Poinsettia plant Clockwise from left: Mistletoe, English holly, winterberries, Poinsettia plant When you think of Christmas plants, what comes to mind? For me, there are three biggies: Mistletoe, poinsettias and holly. But how did these plants come to be associated so strongly with the Christmas season? And is it possible to grow these plants in our yards here in Michigan (and other cold-weather climates)? Here's a look at each of these three festive plants. First, pucker up-- let's step under the mistletoe. Mistletoe is essentially a parasitic plant that attaches itself to a tree or bush and leeches water and nutrients from its host. It's typically been considered a pest species that does little more than stunt the growth and prematurely kill populations of trees and shrubs. However, in recent years, scientists have done studies on the effect of mistletoe on ecosystems, and the results are pretty great. They've discovered that a wide variety of animals depend upon the mistletoe for their survival. The leaves, the shoots and berries provide food for several varieties of birds and animals, helping to create more biodiversity than an area that has no mistletoe present. Certain types of birds, including the spotted owl, also roost and nest in mistletoe shoots. A number of butterfly species in North America also depend upon mistletoe for their survival. Finally, the presence of mistletoe means the host tree has a better chance of spreading its seed; as birds are drawn to the attractive berries of the mistletoe, they are more likely to eat the berries and seeds of the host as well, thus passing seeds over wider areas. Most mistletoe has teardrop-shaped or oval leaves with smooth edges that stay green all winter. The plant produces white berries which are poisonous to humans, but are a valuable food source for many birds. When a sticky seed, found inside the berry, finds its way to a suitable source (the branch of a tree or shrub), it sends out roots into the branch of the host to begin drawing water and nutrients. As the plant matures, it grows into a large basket-like shape that can weigh upwards of 50 pounds. The tangled mass of branches are sometimes called a "witches broom." So how is it these parasitic evergreens have become the catalyst for stolen kisses at Christmastime? Like many non-Christian traditions we find during the Christmas season (decorated trees, lights, a midwinter feast), the tradition has pagan roots. The mistletoe was a symbol of love in Norse mythology. Elsewhere in Europe, the Druids hung it in their homes for good luck and also used it in an elixir to cure infertility. In 18th century England, the serving class began using it as a Christmas decoration, probably due to the lush green color the leaves still bore in December, and started the tradition that a man may kiss any woman standing under a mistletoe sprig. If she refused, she'd be burdened with bad luck. A variation on the tradition suggests that a berry must be removed each time a couple kisses under the mistletoe, and when all berries are gone, so are the kisses. Because mistletoe requires a host plant to germinate and grow, it's not easy to grow your own (at least to cultivate it). It grows best on apple trees, so most farmers that grow mistletoe for Christmas cash crop do so on those. Typically, you would need to find trees with mistletoe already growing in it (easy to spot in the winter when trees are otherwise bare), and harvest it from there. I wouldn't recommend that, however, since it would require special climbing equipment to cut it down. So at the end of the day, this is a plant you're best off buying from a nursery or other store selling holiday foliage. In fact, just leave this plant to the pros. So how about holly? There are several types of American hollies-- two of the most popular are the winterberry and English holly. The winterberry is grown mostly for its bright berries, which grow on thin branches and are great for using in holiday displays and wreaths. The English holly is a bit more of the traditional "holly" look that many people like-- shiny flat leaves with pointy edges, varying shades of green and bold red berries. Different cultivars of English holly can be found in North America, Asia, Europe and North Africa. Growing holly in your yard can add a nice splash of color in the dreary winter months, and add a fullness to your foliage in the spring and summer. Winterberries thrive in wet, swampy conditions, and can do well in shady conditions, although more sun typically means more berries. English holly likes moist, but well-drained, soils, slightly acidic and with ample sun. If you want to grow your own holly bush, you need to keep in mind that most holly varieties require male and female plants growing near each other to produce berries. Only the female plants have berries. The best time to plant holly bushes is in either the spring or fall, when it's cooler and wetter. Like mistletoe, the tradition of holly at Christmas comes from Druid rituals. The Druids would decorate their homes with holly at the winter solstice to ward off evil spirits. Finally, let's talk poinsettias. This plant is a native of Mexico and derives its English name from Joel Roberts Poinsett, the first United States Minister to Mexico. Contrary to popular belief, the bright red (or sometimes orange, pink, white or yellow) petals aren't flowers, but rather leaves called bracts. The bracts derive their color through photoperiodism, which means they require darkness to attain their color (typically 12 or more hours a day of darkness for at least five straight days). At the same time, for the bracts to achieve an optimal brightness, they need a lot of sunlight during the day. The Poinsettia's association with Christmas began in 16th century Mexico, where legend has it that a little girl was too poor to purchase a gift for a celebration of Jesus' birthday, so she gathered wild plants and weeds growing along side the road and placed them at her church altar; through a Christmas miracle, crimson blooms emerged from the weeds and became beautiful Poinsettias. In the 17th century, Franciscan friars in Mexico regularly included them in their Christmas decorations, with the star-shaped petals representing the Star of Bethlehem and the bright red color representing the blood of Jesus' sacrifice on the cross. Poinsettias grow best in tropical or sub-tropical climates, where they won't encounter frost. They can be grown indoors, as long as they can receive abundant sunlight, followed by absolute darkness. During the fall, for the two months leading up to the winter season, they should be exposed to long periods of darkness to bring out their color, followed by abundant sunlight (artificial sunlight is good). And when I say dark periods, I mean the Poinsettias need dark periods! Any incidental light-- television light, light from a neighboring room, a nightlight, etc-- will be detrimental to the plant's color development. Hope your holiday season is great and full of some amazing foliage!  Photo courtesy Rodale's Organic Life Photo courtesy Rodale's Organic Life When we moved into our Zeeland Township property last year, our lawn was in need of a little restoration. To be honest, some spots were in need of a lot. The thing with going organic in your yard, there are no quick fixes; it's always a process. But without chemicals lurking beneath your feet, it's always worth it. One of the things we did was to overseed a few areas last fall that were largely bare and rapidly taken over by big, nasty, hairy, thorny, weedy plants. We spent a better part of the summer pulling those things, and then in late August we threw a seed blend down in order to begin the restoration of that part of our lawn. And now this spring, this section of the yard is thick, lush, deep green and healthy. Those nasty plants that were sprouting up in the bare spots last year? Gone. Now we've got a nice healthy blend of grasses...plus a hefty dose of clover. And you know what? We put put those little clovers there on purpose. Yep, our seed blend was about a third Dutch white clover seed. And no, we're not crazy. Clover is an amazing ground cover! Plus, it pulls nitrogen out of the air and deposits it into your soil-- it fertilizes itself and the rest of your turf! Honestly, a weed is only a plant you don't want. And clover is only unwanted because the chemical industry has told us we should get rid of it. But this little ground cover should be a welcome addition to any healthy, beautiful lawn. Rodale's Organic Life magazine published a story last year which talks about both the aesthetic and scientific benefits of clover in your lawn. Here's an excerpt: The secret to having a great lawn without using harsh chemicals? It's Dutch clover. For the past 50 years, clover has been considered a noxious lawn weed, but before that it was an important component in fine lawns—and for good reason. Clover is drought-tolerant, virtually immune to diseases, and distasteful to common turf insects. And it generates its own food by fixing nitrogen in the soil. So how did this lawn superstar get such a bad rap? Blame the broadleaf herbicides introduced after World War II. Used to kill weeds such as dandelions and plantains, the chemicals also destroyed the clover that was used in many lawn mixes of the time (leaving ugly bare patches in their wake). Today, virtually all seed companies omit clover from their mixes. But that doesn't mean that you can't enjoy the advantages of this great green. Eliminating herbicides from your lawn regime is incredibly easy. And once you do it, most clover you introduce into your back yard will thrive. Here's where to start: Kick The Fertilizer Habit If your lawn is already in decent shape—no big bare patches, less than 20 percent weeds—you can make it organic without adding any new clover or grasses. Conversion is not so much what you do as what you stop doing. In other words, throw out your [chemical] fertilizer... Add Clover + Other Grasses If you're lucky, you already have some clover in your lawn. If not, it's easy to add it by overseeding, or planting on top of what's already there. In spring or autumn, rough up the surface of the lawn with a metal garden rake. Mix the clover seed with sand or finely screened compost to ensure even distribution. Sow two ounces of clover seed per 1,000 square feet for a moderate clover cover, or up to eight ounces if you want the clover to dominate the turf. After sowing, water your lawn deeply and keep the soil surface moist until the clover germinates. The result will be a soft, cushy, deep-green lawn that stays lush through spring, summer, and fall. If you live in west Michigan and you'd like to kick chemical habit with your lawn, get in touch with Good Sweet Earth's turf guy, Steve Veldheer at [email protected]. We can fertilize your lawn without one drop of chemicals-- check out our lawn fertilization service. Let's get the chemical industry out of our yards and go back to doing it the way nature intended!  President Franklin Roosevelt meets with two Georgia farmers in 1932 President Franklin Roosevelt meets with two Georgia farmers in 1932 “To be a successful farmer one must first know the nature of the soil.” -Xenophon (430-354 BC); historian, soldier, philosopher. “The nation that destroys its soil, destroys itself.” -Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945); president. “The soil is the great connector of lives, the source and destination of all. It is the healer and restorer and resurrector, by which disease passes into health, age into youth, death into life. Without proper care for it we can have no community, because without proper care for it we can have no life.” -Wendell Berry (1934- ); writer, activist, academic and farmer. “If I wanted to have a happy garden, I must ally myself with my soil; study and help it to the utmost, untiringly. Always, the soil must come first.” -Marion Cran (1879-1942); first female gardening radio broadcaster, author. “The thin layer of soil covering the earth’s surface represents the difference between survival and extinction for most terrestrial life.” -John W. Doran (1945- ); University of Nebraska agronomy professor, author. “Soil is the last necessary thing. With air and water, a person can live 30 days; add but a comely pile of dirt and life expectancy expands a thousand times.” -Justin Isherwood (1946- ); fifth-generation Wisconsin farmer, author. “You can’t chemical your way out of soil infertility” – Joel Salatin (1957- ); holistic organic farmer, author, lecturer. “If you think organic food is expensive, have you priced cancer lately?” -Joel Salatin. “Each soil has had its own history. Like a river, a mountain, a forest, or any natural thing, its present condition is due to the influences of many things and events of the past.” – Charles Kellogg (1868-1949); Vaudeville performer, naturalist. “We abuse [soil] because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see [soil] as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” -Aldo Leopold (1887-1948); author, scientist, ecologist, forester, environmentalist, University of Wisconsin agricultural economics professor. |